Written by Eleanor Fulvio – 4/1/2024

Grid Resilience and Modernization

As a key component of the clean energy transition, the push to electrify everything historically powered by fossil fuels has garnered significant attention in recent years, especially since the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States about a year and a half ago. Robust grid infrastructure is vitally important to this transition, yet our aging grid infrastructure and the resulting necessity for transmission improvements, represents one of the biggest threats to the clean energy transition we now face. Swift and widespread action is needed from governments and grid operators to bolster and modernize the grid in the coming years in order to support renewable energy deployment and the increased electricity demand arising from the adoption of transportation and building electrification. Moreover, grid reliability and resilience is of the utmost importance for people’s safety and the protection of property, given the strain on the grid caused by the extreme temperatures, weather, and natural disasters exacerbated by climate change. Since certain areas of the country have been disproportionately affected by climate change and grid instability and because access to renewable energy resources is not equally feasible everywhere, grid resilience and expansion is also a critical part of the equitable transition to clean energy.

Understanding “The Grid”

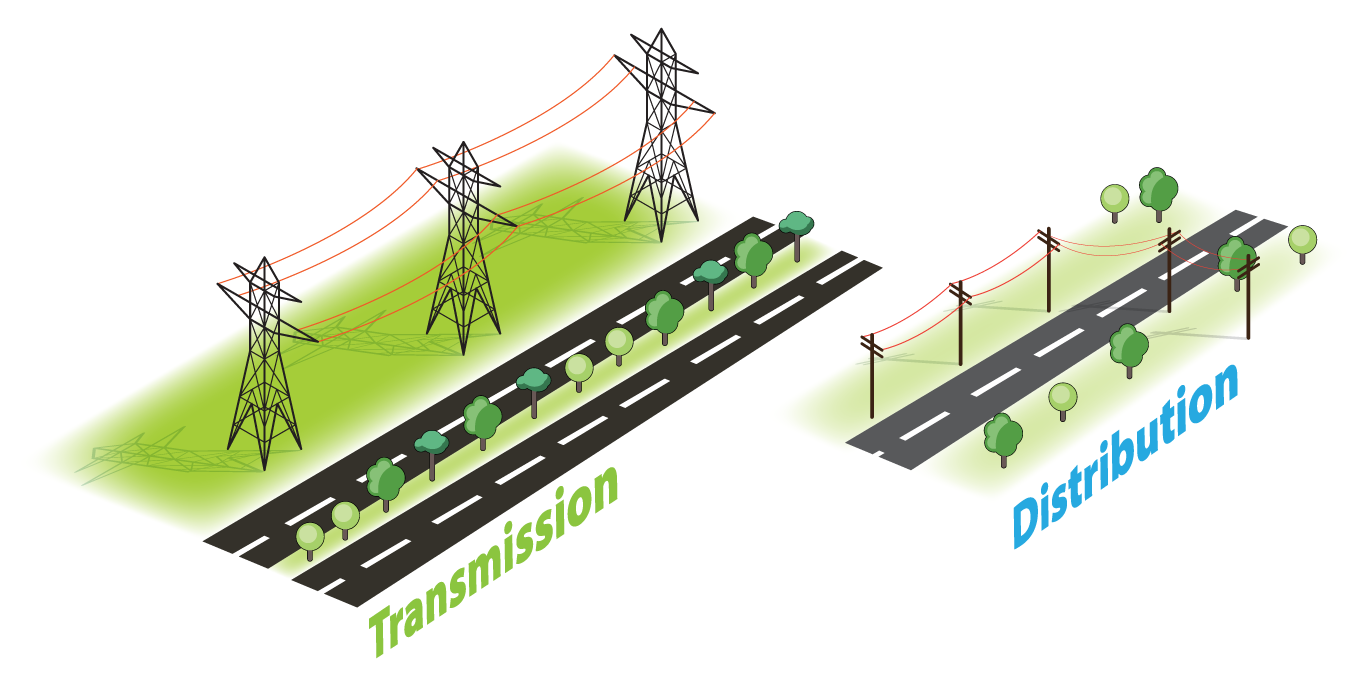

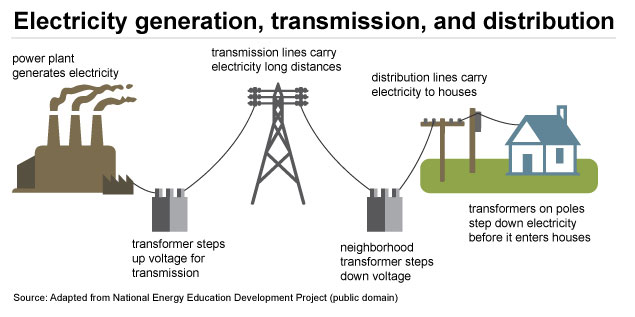

At its most fundamental, what we commonly refer to as the grid in the U.S. is comprised of the high voltage transmission lines that transport electricity from power generators to the substations near areas of energy use and the lower voltage distribution lines that bring electricity directly into our homes and businesses. It’s helpful to think of transmission lines as the interstate highways and distribution lines as the city streets of electricity.

U.S. Energy Information Administration

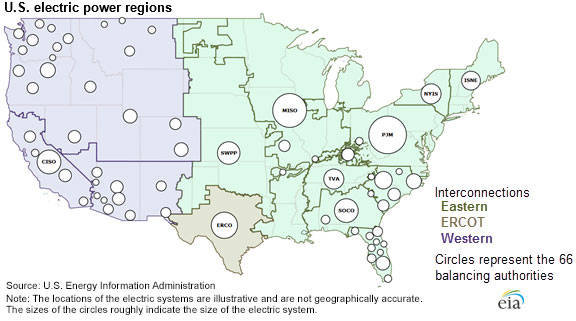

While it may sound simple enough, the grid is actually a complex network of many diffuse local, statewide, and regional actors overseen by state and federal regulatory bodies. Three main interconnections – the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), Western Interconnection, and Eastern Interconnection – make up the highest level of the grid’s structure in the lower 48 states and help to ensure the reliability of the flow of power and decrease the possibility of service interruptions. At the next level of the grid, the balancing of electricity supply and demand is the responsibility of balancing authorities, including utilities and regional transmission organizations, such as PJM, which encompasses Pennsylvania and from whom The Energy Co-op purchases wholesale electricity. Utilities, who are responsible for safety and planning for future electricity needs, must adhere to mandatory grid reliability standards approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and enforced by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC).

U.S. Energy Information Administration

Generation resources are deployed to the grid from lowest to highest cost, with the highest cost resource used at a certain time and location setting the marginal price. When there are fluctuations in demand, transmission, or generation in a certain area, congestion occurs, meaning that the lowest cost generation resource is insufficient to support the energy needs of that area. Higher cost resources are then dispatched in order to make sure all electricity needs are met. With rising numbers of Americans switching to electric vehicles, heat pumps for space heating and cooling, heat pump water heaters, and electric stoves and clothes dryers, congestion is also increasing. The rise in the electrification of homes and businesses is a crucial part of any serious climate action plan but does add strain to the grid. Extreme temperatures, other weather events, or natural disasters like wildfires further stress the grid, exacerbating higher prices and leading to power interruptions and outages. As more aspects of our lives depend on electricity and as the climate changes and creates more extreme conditions, the need for a reliable and resilient electricity grid is becoming exigent.

Current State of the Grid

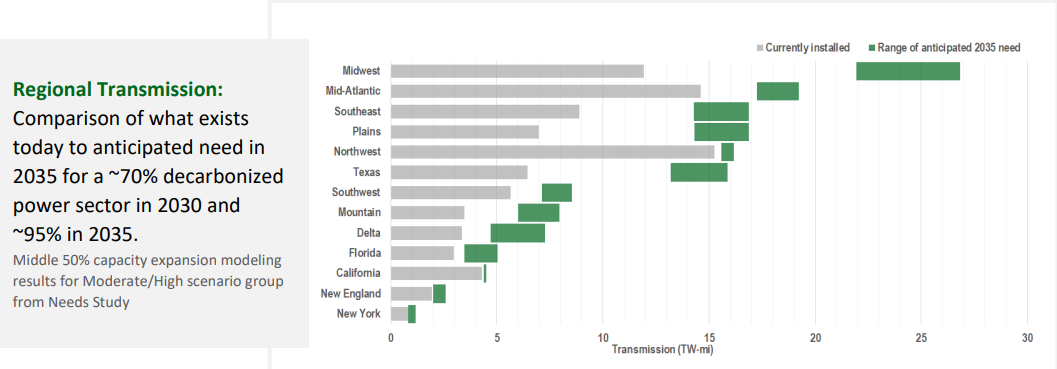

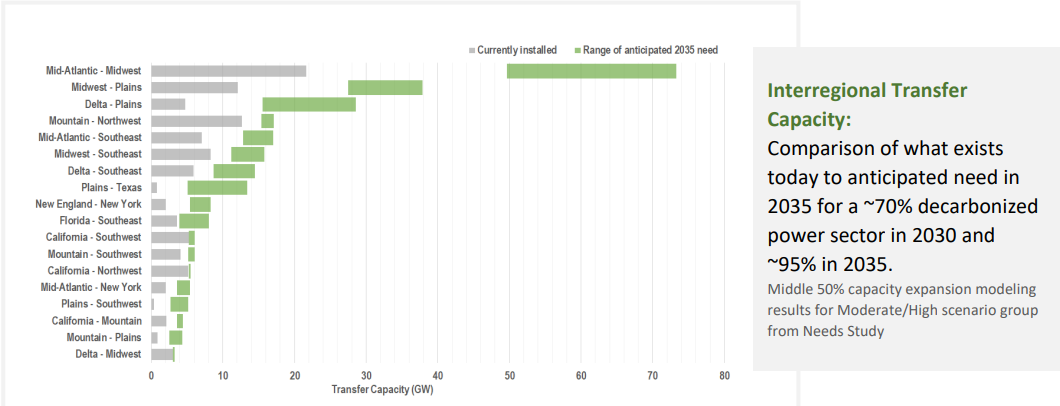

Transmission lines have an expected lifespan of 50-80 years. An estimated 70% of transmission lines in the United States are more than 25 years old, and more than a quarter are 50 or more years old, meaning that a sizable portion of transmission lines is at or rapidly approaching the end of its useful life. The U.S. Department of Energy’s triennial National Transmission Needs Study examines the state of the grid, including capacity constraints and congestion, in order to determine current and future energy needs through 2040 to help guide planning. Per the National Transmission Needs Study released in October 2023, the grid is in dire need of new transmission infrastructure, especially in regards to bolstering regional and interregional transmission. While the needs vary by region over the next decade, significant investment and upgrades will be needed nationwide by 2040. The study found that increased investment could improve reliability and resilience in nearly all areas of the country. Specifically in our Mid-Atlantic region, further investments in transmission between neighboring regions would help alleviate issues during severe weather events, such as those we experienced in the winters of 2018 and 2020. Looking ahead to 2035, in order to support a scenario of moderate load growth and high clean energy growth, transfer capacity between the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest regions will need to expand by 28-51.7 GW, which represents growth of more than 150% compared to the system as of 2020.

In PJM territory, the necessity for greater transmission investment became starkly apparent in the last few years when PJM froze the interconnection queue to additional projects to deal with the backlog of generation projects already awaiting confirmation. Because the vast majority of new projects in the queue are for renewable generation, the old procedure for processing conventional generation projects was not sufficient. This has adversely affected the supply of renewable energy in PJM, which is not keeping pace with demand, and has consequently driven up the price of clean energy.

Challenges to the Grid

Several notable challenges stand in the way of a more reliable grid. It’s clear that new and improved transmission lines are required to ameliorate the dependability of the grid and support a transition towards more renewable generators, but what is less apparent is who should pay for them, how to get them approved and obtain land rights, and how to effectively expand the lines such that clean energy can be deployed at greater distances. Grid security must also be enhanced to protect our power from cyber- and physical attacks. Essentially, these challenges boil down to an absence of clear grid governance, as the authors of a recent white paper released by the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy argue. They demonstrate that the current decentralized system of rules and institutions that govern transmission planning, construction, operation, and maintenance leads to “(1) jurisdictional silos and inadequate coordination; (2) too little public oversight; and (3) misconceptions of the nature of modern reliability problems.”

Jurisdictional silos and inadequate coordination plague the grid because different parts of the grid are controlled by different stakeholders, and different levels of control – planning, building, operating, overseeing, etc. – are also handled by different stakeholders. There are even instances, the authors point out, where nobody has jurisdiction. Planning and building a transmission line involves many stakeholders: one or more utilities, state and federal regulatory bodies, regional planning agencies (ISOs/RTOs), environmental groups, private property owners, etc. Coordination between these parties is at the very least complex and can even be nonexistent or antagonistic. CNBC journalist Catherine Clifford likens the process of building new transmission lines to “herding cats with competing interests.” The situation is worsened when the lines cross multiple states. Not only is it difficult to determine who has jurisdiction but also who benefits from the line and who should pay for it.

Public oversight of grid reliability, the second theme related to grid governance in the Kleinman Center white paper, is virtually nonexistent at present. While the welfare of the public is most at stake in issues of grid reliability, grid governance is highly privatized and opaque. Currently, NERC both writes and enforces grid reliability standards and Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs), where they exist, plan for the grid, operate the markets, and secure resource adequacy. NERC and RTOs are private member organizations and are “dominated by entrenched, large industry players.” Their interests do not always align with the interests of the public at large, which can hinder the very reliability the standards are intended to ensure.

The final challenge highlighted in the white paper is that misconceptions about the nature of modern reliability problems have led to the use of more fossil fuel resources to reinforce grid reliability. This method is fundamentally flawed because, by using new fossil fuel resources to replace old ones, the resilience of the grid is not actually strengthened. On the contrary, one of the real problems hampering grid resilience is that natural gas, which is the top source of electricity generation in the U.S., has also proven to be unreliable in extreme temperatures and weather events. Though switching to renewable resources is not the panacea for solving grid reliability issues, the inclination to believe that more natural gas facilities are the solution is misguided and ignores that natural gas is, in fact, very susceptible to failing in extreme cold.

Solutions to Achieve Greater Grid Reliability and Resilience

The challenges to grid improvement are significant, but many solutions are already underway and ideas abound. For example, as a potential solution to the transmission jurisdictional silo and inadequate coordination problem, the Kleinman Center white paper authors make the case for Congress to give greater authority to FERC to write and enforce reliability standards. Not only should FERC be able to draft technical standards, but it should also have the power to write and enforce performance-based standards. In this scenario, NERC could serve a technical advisory role to FERC. There should also be more standard coordination between FERC, NERC, and other bodies that govern the grid to improve coordination around reliability regulation. Moreover, FERC should have formal regulatory jurisdiction over natural gas transportation, which currently lacks any regulatory oversight.

To address the second issue of a lack of public oversight on grid reliability, the authors suggest strengthening FERC’s oversight of RTOs and NERC and establishing a public office of grid reliability that could also serve the purpose of being a transmission line planning hub. Another recommendation is for NERC and RTOs to start including public representatives on their boards. These improvements would increase transparency so that the grid governing bodies would have greater accountability to the public. Representation would also be more balanced between both public and private interests, leading to outcomes that potentially offer better benefits for all stakeholders.

In terms of correcting the misconceptions about grid reliability that persist, the authors recommend that the toolbox of reliability improvements should be expanded to include solutions like distributed energy resources and microgrids, which can increase reliability and provide resource variability. There should also be methods for holding generators accountable for non-performance and failing to provide electricity when needed, which would address the large-scale power failures like those experienced during Winter Storm Uri in Texas that caused extensive loss of life.

In addition to the solutions proposed by the Kleinman Center white paper authors, improvements are already being ushered in by the federal government. In October 2023, the U.S. Department of Energy announced a $3.5 billion investment in 58 projects across 44 states aimed at grid resilience and reliability. The projects being funded focus particularly on local resilience measures, such as microgrids and distributed generation that allow the power to remain on even if there are outages on the wider grid; wildfire prevention and resilience; and the expansion of clean energy generation, all with the additional environmental justice benefits of encouraging local economic development and the addition of good-paying jobs.

Furthermore, utilities can aid grid resilience by employing time-of-use (TOU) rate plans, which reduce peak demand and promote the use of renewable energy sources by shifting some of the demand to times when certain intermittent generation sources are more available. Lack of consumer understanding of this rate structure presents a hurdle; however, utilities can address it by educating people on how to adjust usage behavior to gain cost benefits, quantifying those anticipated savings, and helping people understand the potential benefits for generation sources and grid reliability.

While these are just some of the ongoing and proposed solutions to improve grid reliability and resilience, building out the United States’s transmission system is arguably one of the most pressing issues of our time upon which the ultimate success of the clean energy transition rests. Without a reliable and more interconnected grid, we will not be able to achieve our climate goals. It is essential for allowing renewable energy resources, like wind and solar, to power even areas where those resources aren’t feasible for power generation at scale. As such, grid resilience and modernization will be instrumental in ensuring that the clean energy transition is effective and equitable.

Cover photo by Brett Sayles