By Lilly Price – 2/28/2025

Air Quality and Environmental Justice in Philadelphia

This blog post will be part of a series exploring current events in environmental justice in the Greater Philadelphia area.

For many consumers, a key factor in choosing the right energy sources is their impact on nearby communities. In Philadelphia, a historic industrial hub, the public health challenges tied to fossil fuel production have shaped the city’s landscape and fueled a strong tradition of community advocacy.

The site of the former Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) refinery exemplifies both phenomena. The site occupies a tract of land larger than Central Park, adjacent to predominantly Black and working-class neighborhoods in South and Southwest Philadelphia. The plant began operations during the Civil War and once processed one-third of all U.S. petroleum exports. It operated as a refinery until 2019 when an explosion released 5,000 lbs. of a particularly lethal industrial chemical called hydrofluoric acid into the air. This incident bankrupted PES Holdings and served as something of a wake-up call for Philadelphia, highlighting the long-term and devastating impacts of fossil fuel production that marginalized communities have endured here and fought against for decades.

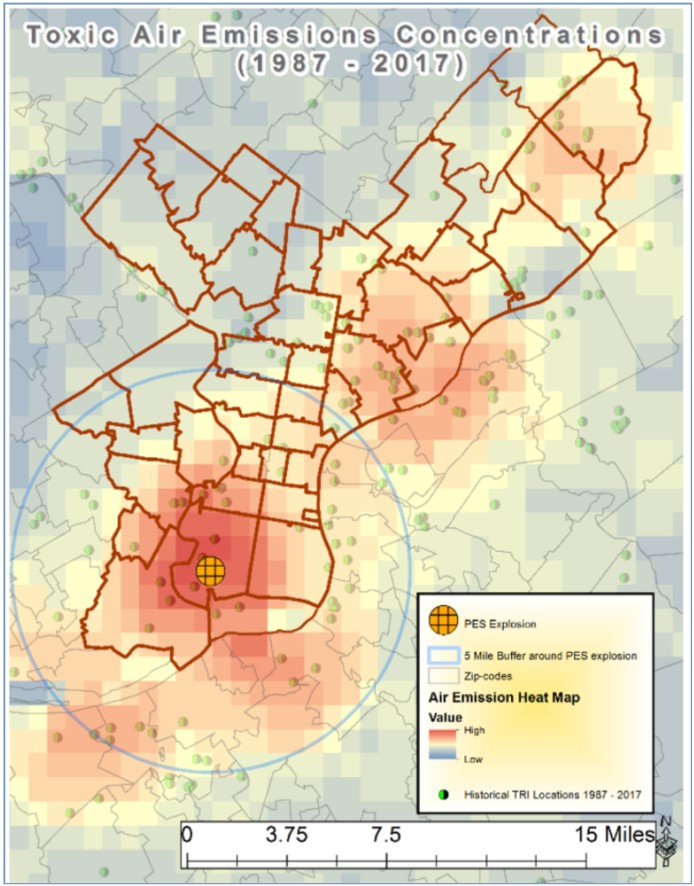

Source: Thomas McKeon with public data from the EPA via The University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. Image included with the permission of the researcher.

Quick Facts

- The PES refinery accounted for 72% of Philadelphia’s toxic emissions in 2016 and was the city’s biggest single source of air pollution for years before its closure.

- The refinery produced 5x the EPA standard of the cancer-causing toxin benzene in 2019, the highest of any U.S. refinery.

- PES racked up $650,000 in fines for violating air, water, and waste-disposal rules in its last four years and was out of compliance with the Clean Air Act for the majority of its recent operation.

Fenceline Communities

For decades, residents of neighborhoods surrounding the refinery, such as Grays Ferry, have reported higher rates of asthma and cancers, especially cancers that are rare or develop earlier than typical screening guidelines suggest. Recent research supports these concerns.

The neighborhoods within one mile of the refinery are disproportionately Black and low-income, a result of Philadelphia’s history of redlining via discriminatory loan practices and the location of public housing. These fenceline communities, named for their proximity to facilities that create hazardous waste, are exposed to significantly higher levels of cancer-causing chemicals than wealthier and whiter areas of Philadelphia.

The concentration of marginalized communities in parts of Philadelphia with high environmental risk factors reflects a national pattern: in the U.S., Black Americans are 75% more likely than the average population to live near toxic release sites. This stark disparity highlights the environmental racism perpetuated by the fossil fuel industry, from places like Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’ to the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Many activists are working to dismantle environmental racism and encourage participation in these efforts, including by sourcing energy from renewable alternatives and supporting organizations that directly advocate for environmental and energy justice.

The Activists

Philadelphians have been organizing to end the damage caused over 150 years at the former PES site. Philly Thrive, a coalition of residents and organizers, is one group leading the charge. After playing a key role in the facility’s permanent closure in 2019, Philly Thrive shifted their focus toward justice in the site’s redevelopment.

“Residents are determined to see the land redeveloped in a way that truly benefits them – they want a say in what gets built on the land, they want to see the land cleaned up, they want to get dignified and safe jobs on the site, and they want to see real investments in their community,” says Allie Naganuma, Philly Thrive’s Campaign Coordinator. Thrive also runs community support programs like summer camps, a gun violence healing circle, a women’s support circle, and a weekly food box delivery. Learn more about their vision here.

Source: Philly Thrive, shared with permission.

When RNG Energy Solutions proposed a biogas plant for lease on the land in 2018 before the explosion, Thrive trained residents to challenge permits and collaborated with thirty other organizations in the Alliance for a Just Philadelphia to present community needs to City Council. Thrive’s lobbying and the extensive media coverage they garnered also helped inform the U.S. Bankruptcy Court’s decision on which developer to permit to purchase the land after the explosion. In 2020, PES sold the site to HRP Group—a real estate development company with plans to develop an e-commerce warehouse and research park—for $225.5 million.

This sale was a major victory for Thrive, but their work did not end there. Redevelopment planning is being closely monitored to ensure that residents’ voices are heard, and that the influx of investment helps restore the health and prosperity extracted by decades of redlining and pollution. “HRP Group has created a “green” community-oriented image to race through the approval process for their redevelopment, and our state and local governments have been giving them all the tax breaks and permits they need to start construction before they have addressed community concerns,” cautions Naganuma.

Source: Philly Thrive’s website, shared with permission.

Although HRP Group has promised “all-inclusive outreach to all stakeholders” to address some of the inherent conflict between profit motives and community interests, Thrive remains skeptical.

“Residents have been asking HRP to hold meetings for years,” notes Naganuma. She reports that to date, there has only been one such meeting, during which residents told HRP that “the number one most important aspect of the redevelopment process was to have ongoing in-person meetings.”

Residents are seeking answers to serious concerns about being priced out of their homes, incomplete cleanup of hazardous waste left by the refinery, and the potential for increased drainage and runoff problems in already flood-prone neighborhoods.

Justice After the PES Explosion & Closure

Communities surrounding development sites can negotiate protections and benefits through a community benefits agreement (CBA), an enforceable contract with developers. CBAs are common in Philadelphia and nationally. Last fall, for example, a CBA with the 76ers for the controversial development of an arena in Center City was initially valued at $50 million. A coalition of community groups seeking agency in negotiations and a $300 million CBA influenced lawmakers to push the Sixers to increase their offer to $100 million. Even so, serious issues with the CBA remained until the arena proposal collapsed.

Developers use strategies to avoid concessions like comprehensive CBAs. They often have complex methods of influencing decision-makers and may “divide and conquer” grassroots alliances, exploit less empowered communities, or offer weak CBAs and non-binding pledges.

Thrive notes that HRP repeatedly promised a CBA but downgraded to a non-binding offer just before City Council was set to vote on HRP’s tax break extension. This last-minute backtracking forced community groups to accept the watered-down deal to avoid losing the leverage of the pending City Council decision. Sixteen groups signed on, including Grays Ferry leader Charles Reeves, who expressed disappointment with the offer: “Do I agree with all the stuff? No,” he said during a City Council meeting last fall, “Is it transparent enough? No.”

Thrive consulted legal expert Julian Gross, who explained that “there’s nothing stopping HRP from modifying or retracting its document. CBAs are negotiated by developers and community organizations, and they each make legal commitments that are enforceable by the other. That’s not happening here.”

Thrive is gearing up for their next phase of action on multiple campaigns and has a message for Philadelphians: “We’re actively looking for volunteers to join our movement. We believe everyone has skills to contribute, and we’d be honored to have you with us. Sign up at bit.ly/PeopesEJAgency to get involved!”

What Comes Next

The sustainable energy evolution brings certain benefits to all of us and to the planet. Yet, we must take care to avoid replicating existing patterns of discrimination as we craft a new energy system together. Energy justice scholars and advocates like Philly Thrive point out that the energy evolution is an excellent opportunity to foster critical awareness and remedy some of the injustices of the fossil fuel system by putting people first.

The Energy Co-op is proud to learn from organizations like Philly Thrive and help our members support and invest in the sustainable energy evolution. Stay tuned for more blog posts exploring these topics, and consider visiting Philly Thrive to learn more.